The past few months I’ve been writing a series of posts about the archetype of the Elf over at my writing blog, and it’s gotten me thinking more about the pagan archetypes and how — and why — we seek to instantiate them. Why do I want to be a Druid? Why do people want to be Witches? What purpose does this desire have in my life, in the lives of others, in society, and indeed ecologically? (Because with all things pagan, we are called to bear in mind the more-than-human world.)

Well, I have some thoughts. I’m going to tackle the Druid first, and then the Witch. This is tentatively planned to be two to three posts, but you know how these things go… There’s a lot to think about. It might end up being a lot more. Thanks for coming along with me on this journey.

Encountering The Wizard

People come to Druidry from lots of different directions. I don’t really know if my path is typical.

I didn’t grow up surrounded by Druids, or knowing any Druids, or even hearing much about them. Nor did I read tons of stories about Druids growing up, or play Druids in video games, or in RPGs. (In fact offhand I can only remember reading about one Druid in literature, and that was Allanon in the Sword of Shannara. A perfectly nice person, but that book was so obviously a knock-off of the Lord of the Rings, and so devoid of the spiritual depth of the original, that it pretty much soured me on all the characters.)

No, it was teachers, explorers, inventors, and scientists I was drawn to. Dahl’s Willy Wonka, Baum’s Great Oz (in the books, where he has a much longer and better redemption arc), Verne’s Captain Nemo, Wells’s Time Traveler, and Asimov’s Susan Calvin and Hari Seldon were people I admired and wanted to be. Either that, or the great scientific detective, Sherlock Holmes. Outside of literature, there was Doc Brown, the Ghostbusters, Obi Wan Kenobi, and Mr Spock (and, later, Geordi La Forge and Data). And I ravenously read scientific nonfiction: computer science, rocketry, and especially astronomy. (Anyone else out there remember Odyssey magazine??)

I wanted to understand why things worked. Geology, history, geography, ecology. The world was dizzying in its wonder and I wanted to find the order, the reasons, the why that I was sure was underlying all of it.

And then, in 1983, when I was about ten, I read the Lord of the Rings. Gandalf was, for me, the central character, the one I most identified with, and who I wished to be. I underwent a radical realignment, and I grew more fascinated with fantasy, history, myth, and language. I went to Earthsea, Pern, Fantastica, Watership Down, Dragonlance, Discworld, and, yes, back to Shannara. I even returned to Oz with new eyes. I reread the Arthurian legends and wondered about the wizard Merlin. Was he just a conjuror, an illusionist, an enchanter? Or did his connection to nature and his commitment to social justice signal something more?

A Different Kind of Man

These characters offered me an escape (in Tolkien’s positive sense, ie as a prisoner might escape) from growing up in the South in the 1970’s and 80’s, and an alternative example of masculinity. When and where I grew up, men had circumscribed interests: sports, machines, and sex. That was it, really. Fast cars, which were machines used for sport, were the quintessential interest of the masculine mind. I often felt I could hardly interact with boys my age without having strong opinions about sports or cars. I went so far as to pretend I liked Porsches just so that conversations wouldn’t grind to a halt when I confessed I didn’t have a favorite type of car.

As for interest in nature, it was forced through an objectification lens: what was this tree, this rock, this land, good for? How could it be used? And of course there was violence. Guns were another machine I had no interest in at all.

And let me be very clear: I was embarrassed about this. It was shameful, and I accepted it as such, to be uninterested in cars or guns or sports or the exploitation of women or forests. But no matter how ashamed I was, I just couldn’t make myself be that person.

But! In these books and stories, I saw a different kind of man, one who was fascinated with the world and how it worked, who was compassionate and wise, who lifted up marginalized and disadvantaged people, and who always sought new solutions for peace.

I didn’t know how to draw a path between where I was and who I wanted to be. I thought maybe I could be a professor one day, if I was lucky. But even in that case, it would be a secular calling, not a spiritual one. I was raised American Zen, and in that tradition, the highest ideal is the lone seeker of enlightenment who meditates on emptiness until the folly of the transient world is transcended. I didn’t want to transcend — I wanted to engage, to reveal, to understand, and to heal.

For Tolkien, the escape of fiction means being shown a better, more wholesome way of being. And the most critical part of that way of being is engagement with the world on its own terms, as researcher, teacher, servant, and transformer.

These are some of the words that inspired me.

Words of Power

If we could fly out of that window hand in hand, hover over this great city, gently remove the roofs, and and peep in at the queer things which are going on, the strange coincidences, the plannings, the cross-purposes, the wonderful chains of events, working through generations, and leading to the most outre results, it would make all fiction with its conventionalities and foreseen conclusions most stale and unprofitable. — Sherlock Holmes

Like Sherlock Holmes, I wanted deep insight that saw to the heart of the patterns of character and society.

Nature’s creative powers are greater than man’s destructive instincts. — Jules Verne, 20K Leagues Under the Sea

Like Captain Nemo, Doc Brown, and Wells’s unnamed Time Traveler, I wanted to retreat into the solitary wilderness to make discoveries that changed the world.

If you define yourself by the power to take life, the desire to dominate, to possess… then you have nothing. – Obi Wan Kenobi

Like Obi Wan Kenobi and the Wizard of Oz, I wanted to work hard to become more knowledgeable, to use my power for good, and to support anyone who needed my help.

The Vulcan philosophical principle of Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations is an ideal based on learning to delight in our essential differences as well as learning to recognize our similarities. — Gene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek

Like Susan Calvin, Data, and Spock, I wanted to understand intelligences that were like ours, but different.

They won’t listen. Do you know why? Because they have certain fixed notions about the past… They don’t want the truth; they want their traditions. — Isaac Asimov, Pebble in the Sky

Like Hari Seldon, I wanted to find the hidden rhythms of history, and make it impossible to repeat the mistakes of the past.

We are the music makers, and we are the dreamers of dreams. — Willy Wonka

Like Wonka, I wanted to inspire people to set aside their greed and self-centeredness, and open their minds to what was possible.

To light a candle is to cast a shadow. — Ursula Le Guin

Like Ged, I wanted to overcome my own demons and defeat the dragons of the world.

A man convinced against his will is of his old opinion still. — Anne McCaffery

Like the Masterharper of Pern, I wanted to teach, to pass down whatever I had learned to whoever could listen.

You that are watching

The gray Magician

With eyes of wonder,

I am Merlin,

And I am dying,

I am Merlin

Who follow The Gleam. — Alfred Lord Tennyson

Like Merlin, I wanted to find prophecy in the wilderness, to teach wisdom to childlike hearts, and follow the fitful, fey trail of inspiration across the waters.

Take this ring, Master, for this is the Ring of Fire, and with it you may rekindle hearts in a world that grows chill. — Círdan the Shipwright (Tolkien’s Silmarillion)

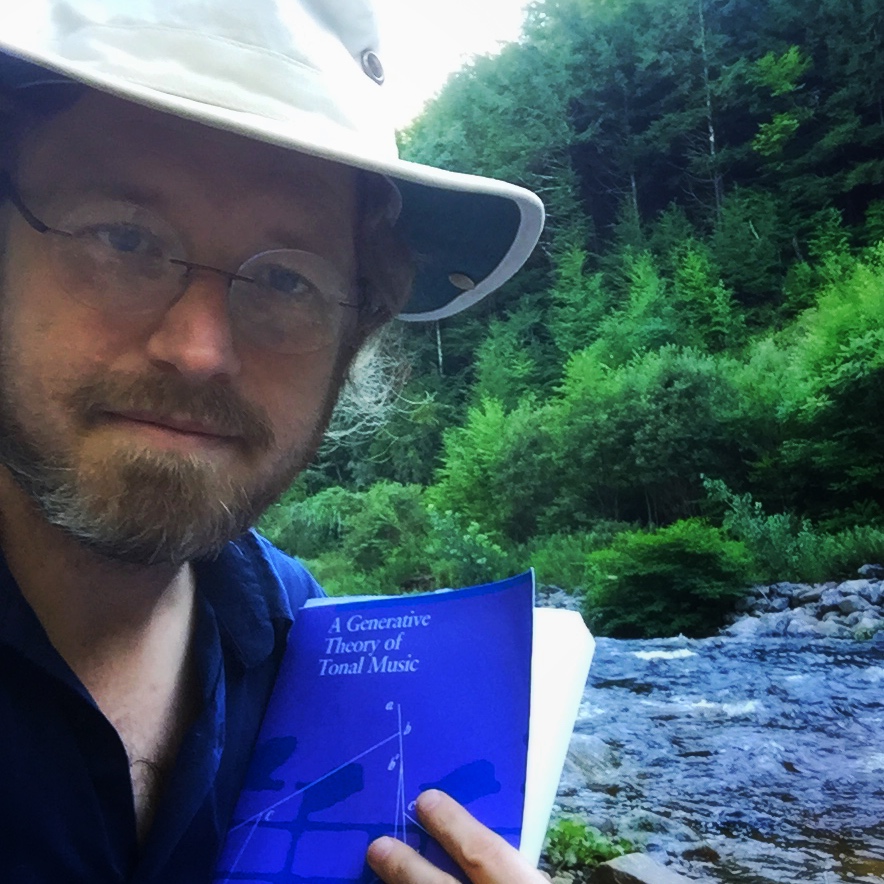

Like Gandalf, I wanted to be at home among all people; to bring wisdom and guidance to all; and to kindle the hearts of others. If I could do this while hiking the mountains with a tall staff, a broad hat, and a book, all the better.

The Unseen Path

Into this heady idealistic mix one must also add the lives of the authors themselves (the mysticism of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the productivity and curiosity of Isaac Asimov, the courage and honesty of Le Guin) as well as psychologists (Jung), mythologists (Campbell), and linguists (Chomsky) whose work inspired me. Tolkien, of course, came closest to having all the ingredients in one package, with his unmatched legendarium and important scholarly philological work. But as a Catholic, he was (for me) insufficiently mystic, insufficiently iconoclastic, and insufficiently interested in the mechanisms of the material and the mind. I still had enough Zen in me, and enough love of nature itself and her inner cogwheels, that I yearned to transcend human understanding, to reach union with the absolute, and to know all the workings of the world intimately.

But I had no road map. I had no guidebook, mentor, or example. I made progress by listening to my intuition, to my body, and to my dreams and meditations. But I was reaching in the dark towards something I wasn’t sure was there.

Around the same time, in the late spring of 2006, I began struggling with a number of issues, including debt, exhaustion, and fear — a lot of fear. I didn’t realize it at the time, but this was the foreshadowing of the end of my first marriage. For no reason I could figure out at the time, I suffered random attacks of panic that were almost paralyzing. (You can read more about this fear, and some of the things I did to overcome it, here and here.) During meditation, I made contact with a spirit / being / archetype who called himself Apollo, and who urged me to create a blog, though he was vague about its purpose. I felt a sense of profound connection, relief, and purpose. (You can read more about this encounter here.) But I still didn’t know what path I was following, or if I was even on one.

So when I randomly picked up John Michael Greer’s Druidry Handbook, it was a thunderclap.

(cont’d in next post)

Leave a comment