It’s been a minute since I’ve discussed the power of story and storytelling in this blog; most of my musings on that have been carried on over at Axon Firings. You can find a few of my earlier thoughts here and here. But I had some fiction-inspired thoughts this morning that have, I think, broader relevance to the spiritual community. What I want to address here is the nothing less than the role of godhood. What are gods like? What do they do? And how do they interact with us and create meaning in our lives?

If you’re a follower over at Axon Firings you know I’m working on a fantasy novel called “Crown of Crows” which was heavily inspired by Lewis’s Narnia. In fact it started out as fanfic: I wanted to address Narnia from a pagan and feminist point of view by looking at what happened to poor Susan. Obviously many other authors have tackled this but I have my own take on things, as you have seen if you’ve been following the story’s progress on my Patreon. Eventually, however, I determined the story would be stronger (and I would be less open to copyright infringement!) if I moved the book away from “fanfic” and reworked it into its own thing. Aslan had to go, of course. (I also tossed the wardrobe. The Witch I figured I could keep.) At first I just changed his name, but in the end I decided to make him a Bear. It would be hard to confuse a Lion with a Bear.

Why a Bear? Well, I like bears and I’ve met bears and while I’d never claim to know them well, I certainly know them better than lions. Like lions, they’re large apex predators and command a lot of respect, and I could imagine a bear fulfilling many of the story roles that Aslan did in Narnia.

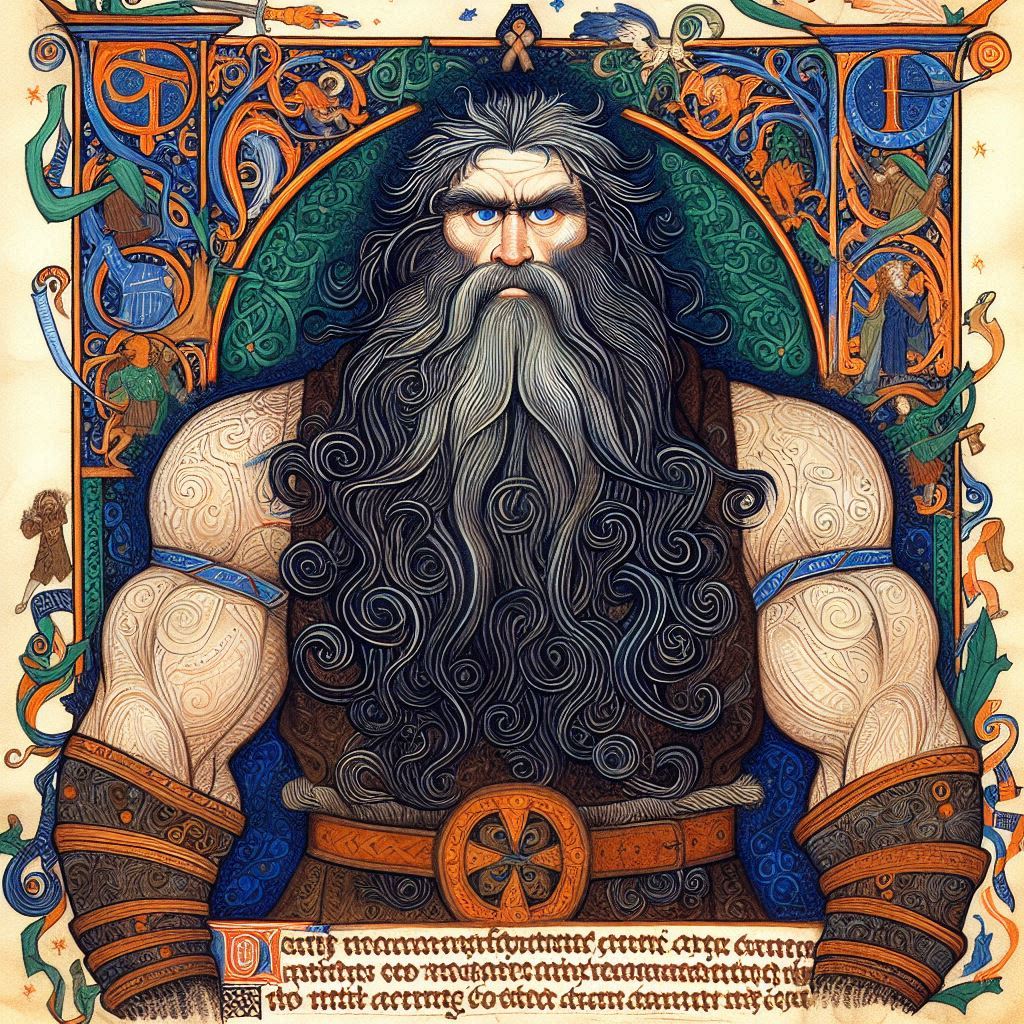

But I found that once I’d made the change of species, other changes had to be made. For starters, his name could no longer be Aslan (since that’s Turkish for Lion, and in any case probably trademarked). So I worked out a new one for him: Antahr, which comes from Old Irish an t-ár, “the Bear.” (Old Irish ár is related to Welsh Arthur, so there’s a great kingship connection there.) Antahr. Antahr. What manner of spirit is Antahr?

Bears are actually quite different from lions. Lions travel in prides, are carnivorous, and prefer grasslands where they can see and travel far. There are huge differences in behavior and appearance between the gender roles: female lions hunt and protect the young; male lions mostly fight other male lions. Bears are much more solitary (except for a mother bear with her young cubs). They are omnivorous, eating mostly berries, fish, and small mammals. They prefer forested areas with rich access to their favorite foods, and they are fine having overlapping territories as long as they can easily avoid each other. Males and females lead much the same kind of life, other than child-rearing.

Let’s look briefly at how the lion and bear are portrayed in the Bible, in Lewis’s work, and in Tolkien’s work, and then consider what these themes mean for the narratives we weave about godhood.

Narnia and Judah

“Then one of the elders said to me, ‘Do not weep! See, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has triumphed. He is able to open the scroll and its seven seals’” (Revelation 5:5).

You can see the character of the lion reflected in Christian lion symbolism, and similarly in Aslan. Jesus is known as the Lion of Judah because of the lion’s association with authority and kingship — the apex predator on top of everyone else — as well as its strength and courage, showing Christ’s power over evil. Jesus is said to protect the faithful as a lion protects its pride. The fierceness of the lion is reflected in the idea that Christ’s justice can be ferocious as well as merciful.

Reading this description, the character of Aslan seems to leap off the page. He is the very personification of authority and kingship: he arrives, takes charge, defeats the White Witch with ferocity (stopping only briefly to be murdered and reborn), extends mercy to her followers, and then installs the Pevensie children as kings and queens to rule and his stead.

The Bear is a very different beast. The bear occurs more rarely in the Bible and has a more limited range of meanings. It’s mostly used as a metaphor for God’s judgment, showing the power and wrath of God’s punishments. One of the few examples occurs in 2 Kings, when Elisha curses a throng of children who have been mocking him, and God sends two “she-bears” to punish them, mauling 42. In another case (7 Daniel), the bear appears in a prophetic dream representing a ruthless Empire. Clearly, for biblical peoples, bears are ferocious, merciless beasts.

Interestingly, in Lewis’s Narnia, bears are treated more like teddy bears than anything else. There are, for example, the Bulgy Bears who help Aslan and the Pevensies against the White Witch, and who cannot stop sucking their paws; and there are the bears at the dawn of time who cannot decide what kind of animal Uncle Andrew is and treat him as a pet or a toy. Prince Corin of Archenland famously defeats the Lapsed Bear of Stormness in a boxing match, after which he is a “reformed character.”

Since Lewis echoes the Biblical symbolism of lions so perfectly, it’s odd he is so much more cuddly and playful with his bears. Where does that come from?

Arda

The lion, for Tolkien, is an afterthought. It appears in one poem (“Cat”) and he did create an Elvish word for it (Rávi in Quenya; probably onomatopoetic). The symbolism of the lion clearly didn’t resonate with his vision of godhood.

But the bear is another story. Beorn the skin-changer is an excellent example: inspired partly by the Norse berserkers (literally “bear-shirters”) who fought like ferocious beasts and seemed immune to all weapons, and partly by the ecology of the bear itself with its omnivorous, honey-loving, loner habits, Beorn is a mix of man and bear who is completely self-sufficient and master of his own little land by the Great River. He shares his home, his fire, and his food, and his good advice to Bilbo and his companions in exchange for nothing more than a great tale.

Interestingly, Beorn (whose name is Old English for man, warrior but sounds almost exactly like Old Norse bjorn, bear; Old English for bear was bera) also leads a moonlight bear dance around his property — dozens of bears of all kinds dancing from dusk till dawn outside, while Bilbo and his companions slept inside. This is echoed in one of Tolkien’s latest writings concerning Númenor, in which he states that the bears of Númenor were friendly with the humans and would dance for them and with them on special occasions. The dancing bear is a symbol found throughout Europe, North Asia, and North America, usually representing an intimacy between the human and natural world.

In fact the bear is an exceedingly rich and complex symbol in the old paganism of Europe and Asia. Along with all the associations listed above, the bear is also associated with kingship, particularly in Celtic lore: thus the mightiest king in English folklore is named Arthur. As a fierce warrior, he reflects the fierce protection the mother bear offers to her cubs. As the once and future king, he reflects the hibernation pattern of the bear. The bear is also connected to healing and medicinal herbs, meditation, and vision journeying. It can be found in the northern stars, midnight, and the winter solstice; it is the guardian of treasures; honey, mead, amber and eternal life; and transformation, particularly from bear to human and back again. (You can see Beorn reflecting so many of these associations: Tolkien knew his stuff.) Less commonly, but just as essentially, is the wedding between the male bear and the female human, which is found in many myths and legends worldwide.

Sagaia

So: what did I want to do with Antahr in this story?

- Power. He is a strong, powerful figure of authority.

- Guardian. He is one of the guardians of Sagaia — not the only one, but an important one.

- Conflict. As a powerful guardian, he naturally becomes involved in conflict. He is in conflict with external threats, but also with others in Sagaia who may disagree with his methods or aims.

- Complex Relationships. I wanted to show that Antahr, like all beings in a pagan (and natural) world, is part of a complex web of relationships. It’s not just him at the top and everyone does what he says.

- Leadership. Nevertheless he IS a leader. He has direct followers, such as the nobles and monarchs of Sagaia and the animals who love him, and allies like other spirits and guardians, and others who may or may not join his cause. He needs to show how a strong leader navigates these complexities.

- Transformation and Redemption. Antahr’s actions may be connected to the end of the world, and he is working to prevent it or, if possible, undo it entirely. Thus, unlike Aslan, he has a character arc and a path of learning to walk.

Earth and Godhood

What does this say about the character of godhood, and the symbols we use for it?

First of all, it is clear that when a Christian says “Jesus is the Lion of Judah,” or I say “Bear is a powerful spirit,” we are not saying that these deities are literally lions (or tigers) or bears. We as humans are using these animals as a way to grasp part of the character of these gods. A lion is powerful; Jesus is powerful; and the better we know the strength of the lion, the better we know the strength of Jesus. The better we know the gentle fierceness of the bear, the better we know the gentle fierceness of the landscapes and forests where his spirit walks. And I do not think that these connections exist only in the mind of humanity. I think that these animals have the characteristics they do in part because of the spirits that animate them, as they animate us. We do truly sense the links between the gods and these animals.

In reshaping Aslan into Antahr, the Bear, writing his dialogue and watching how other characters interact with him, I saw a new spirit speaking from the page. Antahr had strength in his solitude; and he transformed himself through introspection. And he highlighted the connection between humanity and nature in a new way. The lion exerts dominance and kingship from a distance; but the bear invites us into a much more intimate relationship. This is perhaps by Lewis’s bears are cuddly paw-suckers, and Tolkien’s lions are found only in his marginalia*.

I do not intend to reduce Christianity and Paganism to these animals. Obviously the Lion is not the only symbol of the Christian god, and the Bear is not the only spirit that walks the forests. A god, any god, is more than a single mortal animal, or even an animal’s archetype. But a symbol is a critical point of connection: a place where you touch and communicate with spirit. If the Lion is your main connection with the Christian God, he will protect you, but he will remain distant and lordly. If the Bear is your main connection with spirit, you will be transformed and drawn into an intimacy and raw strength you may not expect. Choose your guides carefully, if you can, for they walk beside you in your life and in your dreams.

*(Tolkien’s symbols of kingship are, in any case, not animals, but stars, as you can see with the greatest kings of Elves, Men, and Dwarves: Gil-Galad, Aragorn and Durin. Recall that bears are associated with stars as well.)

Leave a comment